South Korean cinema: Challenges beyond rapid growth

With Parasite winning four Oscar Awards, including a historical win of the Best Picture, South Korea is standing at the spotlight of today’s film industry.

In his Best Director acceptance speech, director Bong Joon-ho thanked Korean film audience for their support and straight-forward opinions. Indeed, South Korean moviegoers are among the most enthusiastic groups. An average citizen visits cinemas over four times each year, a number that tops the world.

The success of Parasite is not duplicable, nor is it the ultimate goal. Looking at the top 500 highest-grossing films in the market, challenges are still unfolding.

Dazzling Leaps

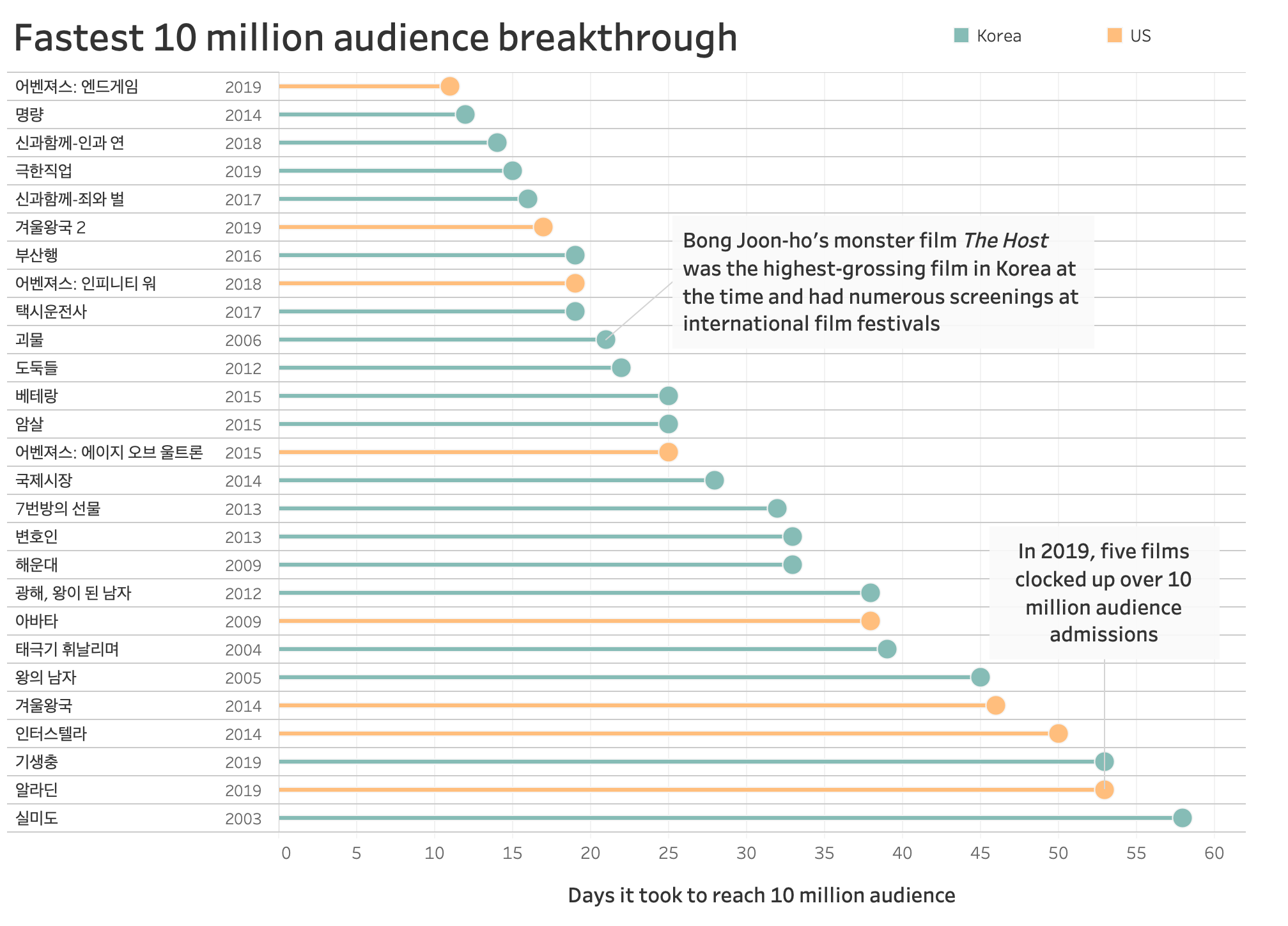

South Korean film industry celebrated its 100th anniversary in 2019, but it was in the past two decades that it started to make its mark on the global stage. Director Lee Chang-dong was awarded the Silver Lion for Best Direction with his film Oasis in 2002. Park Chan-wook's Oldboy won the Grand Prix at the 2004 Cannes Film Festival. Bong Joon-ho’s monster film The Host in 2006 marked the prelude to his global journey.

Despite former president Park Geun-hye’ blacklist of artists, Korean filmmakers have been able to leave solid footprints in history and bring the their culture to a wider audience. They are not only applauded for the stimulating action scenes, but also the vivid depiction of human nature and the honest portrait of the society.

According to the Box-office Information System under the Korean Film Council, 27 films have reached the threshold of attracting 10 million audience, two thirds of which were domestic production. In a country with a total population of around 51 million, it means every one out of five people have watched the film. Last year, Avengers: Endgame set a new record by achieving the milestone in 11 days, one day faster than The Admiral: Roaring Currents (2014).

Smokeless Battlefield

In the last century, filmmakers participated in waves of demonstration to protect the domestic film industry from the “Hollywood invasion.” The efforts resulted in the establishment of film promotion laws, the abolition of censorship and the well-known “Screen Quota” system. Cinemas were required to show Korean films for at least 146 days each year, which was reduced to 73 days in 2006 when the market share grew steady.

Domestic and overseas films screened in Korea are continuously on the rise. But the growing import of foreign films and imbalance in screen distribution have once again triggered a warning for domestic filmmakers.

One of the reasons that films are occupying more screens is simply more cinemas are being built. The total number of cinema screens across the country has increased from 1974 in 2011 to over 3100, according to KOBIS.

The top 30 films with the maximum number of screens in the first week after release mainly came after 2017. A majority of them were from the U.S., with the top three being Avengers: Endgame (2019), Frozen II (2019) and Avengers: Infinity War (2018).

When Disney animation Frozen II swept Korean cinemas last November, it also ignited controversies and protests among Korean filmmakers. Civic group Public Welfare Committee filed a complaint against Walt Disney, claiming that the film violated Korea’s anti-monopoly law by occupying 88% of domestic screens on its opening day.

Presale tickets and online popularity will be reflected in the number of screens reserved for each film. More screens tend to attract more audience because they have limited choices. As domestic films enjoy fewer screens than their counterparts, people have started to call for new measures torestrict foreign films.

On the other hand, most successful films rely on large distributors, such as SHOWBOX, CJ, Warner Bros and Lotte. Independent filmmakers and theaters expressed concerns that the oligopoly has left them limited room for profits.

Last year’s domestic blockbuster Extreme Job generated KRW 140 billion (USD 114 million) on a production budget of KRW 6.5 billion (USD 5.8 million), but such luck is not easy to come by. Critics are worried that more and more films are unable to reach the breakeven point, and the lack of revenue will lead to hesitation in investment.

In February, over 1,000 South Korean filmmakers put forward a “Post Bong Joon-ho Act” in a request for balanced screening distribution, limiting screen monopoly on large companies, and creating a fair environment for rethinking film market diversity.

Silver Lining

After the Oscars ceremony, South Korean President Moon Jae-in wrote on Twitter that the government will “stand with those in the film industry so that they can stretch their imagination to the fullest and make movies free from worries.”

The statement was well received among netizens, and it was not unfounded. Regional film commissions provide environment and assistance for film production in major cities. International film producers are welcomed in Korea with official shooting guides prepared for them.

But the Korean film industry is still faced with various challenges. The threat of online piracy, tight schedules and high production cost all seem to get on filmmakers’ nerves. Whether emerging talents can benefit from existing policies and realize their dreams remains to be seen.

Cinemas had hardly benefited from Parasite’s success when they got hit by the coronavirus. Anticipated films and shooting plans are postponed, audience are turning to streaming platforms at home, and distributors are considering new possibilities for film release. But this could also be a chance for the industry to reconsider its next moves.

At a press conference after the triumphant return, Bong suggested that there should be more interaction between independent and commercial films, so that young directors can give full play to their creativity. “The mainstream film industry needs to stop fearing risk and embrace challenging films.”